New Insights on Targeting BRCA-Mutant Cancers

Scientists at UMass Chan Medical School have made a groundbreaking discovery that challenges conventional understanding of how anticancer drugs destroy BRCA1 and BRCA2-mutated cancer cells. Their research, published in Nature Cancer, reveals that rather than double-strand DNA breaks being the primary cause of cancer cell death, single-strand nicks that expand into large single-stranded DNA gaps drive this lethal process.

Unpacking BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations

BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are widely known for their role in DNA repair. When functioning correctly, they help fix damaged DNA, preventing harmful mutations that could lead to cancer. However, mutations in these genes significantly increase the risk of breast, ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic cancers. Because BRCA-deficient tumors have trouble repairing DNA damage, they are particularly vulnerable to DNA-targeting drugs like poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (PARPi).

For years, scientists believed that the effectiveness of PARPi stemmed from their ability to cause single-stranded DNA breaks, which then progressed into damaging double-strand breaks. However, this new study suggests an entirely different mechanism is at play.

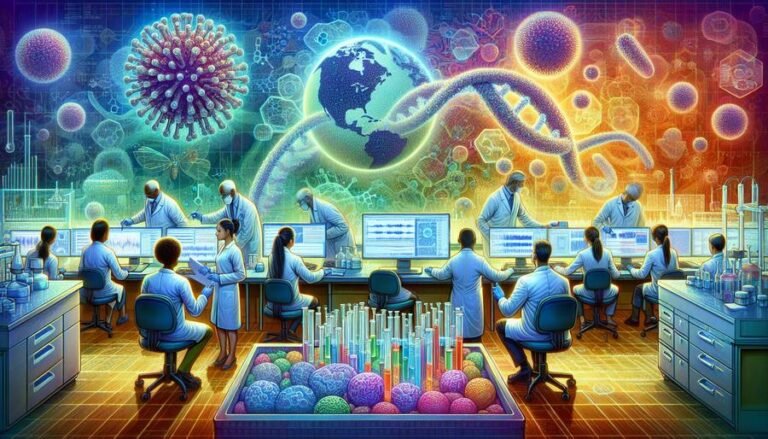

A Shift in Scientific Understanding

Dr. Sharon Cantor and Dr. Jenna Whalen sought to understand how exactly small DNA lesions led to cancer cell death. Using CRISPR gene-editing technology, they precisely introduced single-strand nicks into various breast cancer cell lines, including both BRCA-deficient and BRCA-proficient cells. Their results were startling—the BRCA-mutant cancer cells were extremely sensitive to these small nicks, even before they transformed into full double-strand breaks.

This sensitivity arises because BRCA1 and BRCA2-deficient cells struggle to properly process these small nicks. Normally, cells repair minor breaks in DNA without issue, but in BRCA-deficient cells, excessive resection (the trimming of one strand of DNA) occurs instead. This leads to the formation of large single-stranded gaps, which ultimately triggers cell death.

“Our findings reveal that it is the resection of a nick into a single-stranded DNA gap that drives this cellular lethality,” Whalen explained. “This highlights a distinct mechanism of cytotoxicity, where excessive resection, rather than failed double-strand break repair, underpins the vulnerability of BRCA-deficient cells.”

New Avenues for Cancer Treatment

This discovery is particularly exciting because it highlights a new therapeutic target. If BRCA-mutant cancer cells are uniquely vulnerable to single-strand DNA nicks, then treatments designed to introduce these nicks—such as ionizing radiation—could be an effective strategy against drug-resistant cancers.

One of the biggest challenges in treating BRCA-related cancers today is drug resistance. Many cancers that initially respond well to PARP inhibitors develop resistance over time, regaining DNA repair capabilities and making them harder to treat. However, this study suggests that even PARPi-resistant cells with restored homologous recombination are still highly sensitive to nick-induced damage.

“Our findings suggest a path forward for treating PARPi-resistant cells that regained homologous recombination repair: to kill these cells, nicks could be induced such as through ionizing radiation,” Cantor stated. By harnessing the power of these small but fatal DNA lesions, researchers may have uncovered a way to combat recurring and treatment-resistant cancers.

Implications for Future Cancer Therapies

The study’s findings raise a host of new possibilities for cancer treatment strategies. If scientists can develop therapies that precisely induce single-strand nicks in cancer cells, they may be able to selectively target BRCA-mutant tumors without causing excessive collateral damage to healthy cells. Additionally, combining PARP inhibitors with other treatments that create DNA nicks could lead to a more potent anticancer response.

This research also underscores the importance of revisiting foundational scientific assumptions. Despite decades of believing that double-strand breaks were the key mechanism of PARPi-induced cancer cell death, experimental validation was lacking. Thanks to advanced genome engineering tools such as CRISPR, scientists now have the ability to test and refine these theories, leading to more effective treatments.

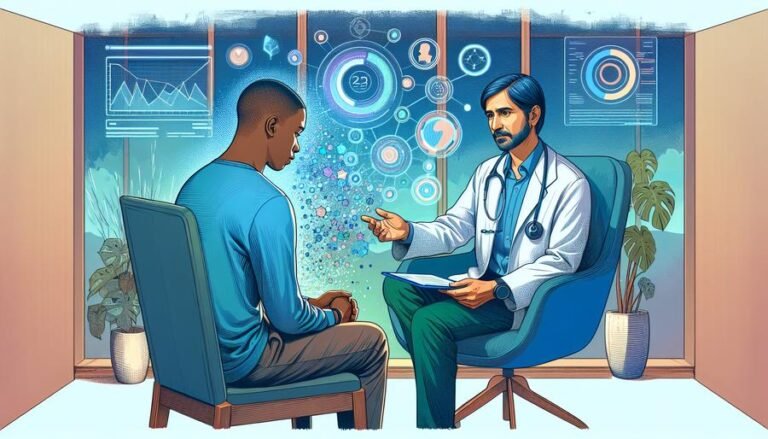

A Step Toward More Personalized Cancer Care

Cancer treatment is increasingly moving toward a personalized medicine approach, tailoring therapies to the genetic profile of an individual’s tumor. This study supports the idea that treatment strategies should be refined based on the specific vulnerabilities of cancer cells, such as their inability to process single-strand DNA damage.

The potential takeaway for patients and oncologists alike is that future therapies targeting BRCA-mutant cancers may not only involve PARP inhibitors but also other treatments that exploit single-strand DNA nicks. If these findings translate successfully into clinical settings, they could lead to more effective treatments with fewer side effects.

In summary, this research shifts our understanding of how anticancer drugs work and sheds light on a new vulnerability in BRCA-mutant cancer cells. By exploring therapies that induce single-strand DNA nicks, scientists may unlock new ways to fight drug-resistant cancers, offering hope to patients whose tumors no longer respond to conventional treatments.

For more details, read the full study in Nature Cancer.